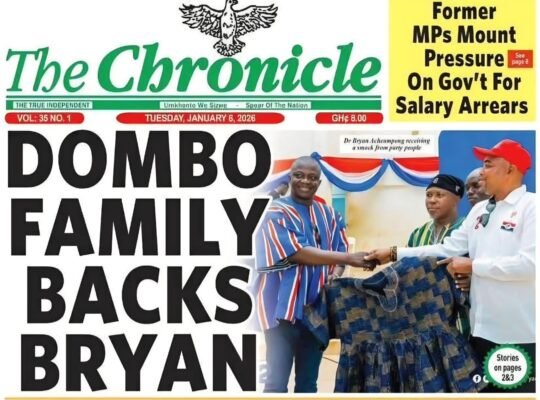

Opinion by Latif Mahama (Journalist)

For over two decades, I’ve chronicled the heartbeat of the Upper West region as a journalist, and one issue has pulsed louder than any other: the deplorable state of its roads. From dusty trails to pothole-riddled stretches, these arteries of connectivity—or lack thereof—have become a symbol of neglect, frustration, and unfulfilled promises. The people of Upper West, from farmers to chiefs, civil society to traders, have cried out for change, with their voices echoing through press conferences, demonstrations, and heartfelt pleas to successive presidents. Yet, the roads remain a stubborn scar on the region’s landscape, a barrier to progress, and a daily reminder of broken trust.

The Upper West, often hailed as one of Ghana’s food baskets, is tethered to its crumbling infrastructure. Farmers, the backbone of this agrarian region, struggle to transport their produce to market centers. The perilous state of roads like Wa-Han-Tumu, Wa-Bulenga-Kundugu, Tumu-Gwollu-Jefisi, Wallemboi-Nabulo-Sandema, Lawra-Domwine-Han, Wa-Dorimo-Wechiau and Wa-Bole-Bamboi forces road users, particularly farmers to endure long, costly journeys, only to face traders who exploit the situation, offering rock-bottom prices for their harvests. This vicious cycle has rendered farming— an industry with deep cultural roots and immense potential — unattractive, particularly to the youth.

In a region already grappling with astronomical poverty levels, the poor road network stifles economic growth and widens the development gap between Ghana’s north and south. The human toll is equally devastating. Access to quality healthcare is a distant dream for many, as the treacherous roads delay critical referrals to district hospitals or the regional hospital in Wa. Avoidable deaths are not uncommon, with travel times turning minor emergencies into tragedies. Social and cultural life suffers, too. Weekends see a grim parade of accidents as families brave dangerous routes to attend funerals or connect with loved ones, defying the risks to honor tradition.

The revered chiefs of Upper West, from Tumu to Nandom through to Lawra, from Jirapa, Nadowli, Issa, Wechiau, Funsi as well as Lambusie have not been silent. Their meetings with presidents, including visits to the Jubilee House, are punctuated by pleas for better roads — pleas that too often fall on deaf ears. The litany of unkept promises is a bitter thread in this narrative. In 2012, then President John Dramani Mahama stood before a hopeful crowd in Tumu, pledging to fix the Wa-Han-Tumu road within his first term. The chiefs, moved by his words and his shared Gonja heritage, gifted him a smock but withheld the accompanying hat, a symbolic gesture to hold him accountable. The people of Sissala East voted for him, trusting their “Gonja brother” to deliver. Yet, the road remains incomplete, and the hat still rests in the palace of Kuoro Richard Babini Kanton VI, a quiet rebuke of unmet expectations. Similar pledges came from President Nana Addo Dankwa Akufo-Addo and former Roads and Highways Minister, Amoako Atta. On one visit to Tumu, the minister’s Toyota Land Cruiser V8 suffered a puncture at Jeffisi, a moment locals wryly called the “cry of the gods” for urgent action. Yet, the Wa-Han-Tumu road, like many others — Wa-Bulenga-Kundugu, Wa-Wahabu-Funsi, Gwollu-Jeffisi, and beyond—remains a patchwork of neglect. The current Roads Minister, Kwame Governs Agbodza, announced rehabilitation work on the Wa-Bole-Bamboi-Techiman road would begin in June 2025. Four months later, the road, a nightmare for travelers, shows no signs of progress.

The question looms large: What price must Upper West pay to have its roads fixed?

The eleven districts of the Upper West are united by this shared plight. Poverty, already a heavy burden, is compounded by infrastructure that stifles opportunity. Some roads were awarded to contractors, but work has stalled, often due to government’s failure to pay. If contracts have been terminated, the silence from the government is deafening. As the wise say, “He who pounds for a blind man must keep talking, lest he be accused of eating.” Communication is not just courtesy—it’s a necessity. For the people of Upper West to believe in initiatives like the current John Mahama-led “Big Push,” the government must honor its financial obligations to stalled projects. Transparency is critical. If contracts are canceled, the people deserve to know why.

The Upper West region’s patience has been tested by decades of rhetoric without results. The roads are more than infrastructure; they are lifelines to markets, hospitals, and cultural traditions. They are the path to closing the north-south divide. As the sun rises over the region, it illuminates not just the beauty of its landscapes and the beautiful culture of the inhabitants but the resilience of its people. They have spoken, marched, and pleaded. Now, they ask: What more must we do? The answer lies not in their sacrifice but in the accountability of president John Dramani Mahama and all those who hold the power to pave the way forward. Let the roads of Upper West be a priority—not a promise left to gather dust like the smock’s hat in the palace of the paramount chief of Tumu, Kuoro Richard Babini Kanton VI.